P3s: How do we create better conversations between governments and investors?

Unsurprisingly given this context, there is a tremendous amount of interest and excitement about public-private partnerships (P3s) as potential magic solutions. To the uninitiated, these arrangements may seem to promise new and risk-free sources of capital that can be used to build signature projects that will improve productivity, unleash innovation, and deliver votes.

But the reality is, most public officials still don’t appreciate how the interests of the private sector condition their willingness to participate in P3 arrangements. The result is usually an ongoing series of unproductive conversations and delays in realizing the infrastructure we need.

My company, Hatch, is a global engineering and technology firm. We have a long and deep history of involvement in infrastructure projects, starting with very early transit development programs in North American cities. We feel that we’re well-positioned, through the global planning and advisory practice which I lead, to help governments, investors, builders, and developers structure and realize important public-private partnerships.

Let’s begin at the beginning, by suggesting some basic insights into effective P3s.

Financing and funding

Wherever you find governments enthusiastic about exploring P3s, you can safely bet that their primary interests are finding new sources of funding. They face rising costs to maintain existing assets. They’re reluctant to use revenue tools to source new capital, and they want to believe that the private sector will see the value in investing in new infrastructure projects.First, many governments fail to appreciate how the private-sector components of P3s deliver real, tangible benefits with their design-build-finance-and-maintain models. The single, most important way they do this is by enabling the big risks of construction and maintenance to be transferred from government to them, the private-sector partners. These risks—construction and maintenance—are the very elements that invariably lead to huge cost and schedule overruns when governments deliver the projects themselves.

Secondly, P3s force groups of talented designers, builders, financiers, and maintainers to come together to respond to RFPs, thereby creating competitive tension both between and within the consortia. This reliably translates into bids that have lower costs and greater innovation.

Third, P3 project agreements force governments to be disciplined and specific about the design, construction, operations, and maintenance outcomes they are seeking to achieve. The typical P3 procurement process also allows government to triangulate the cost of its desired outcomes and specifications by collating the feedback of multiple bidders in response to a common draft project agreement.

Finally, the arrangements have fiscal profiles that are beneficial to political leaders. Rather than paying costs as they come up, governments are able to recognize them over a longer period of time. In all cases, substantial completion payments (which typically represent a considerable portion of the costs) are only paid once a government is satisfied that the assets have been built to its satisfaction.

For P3s that meet these criteria, there is a robust community of investors that is more than willing to provide financing to government. Since the inception of the program in Ontario, Canada, close to $3 billion worth of infrastructure projects have been financed by P3s. Half of this money has come from investment funds, 31% from insurance companies, 12% from banks, and 7% from pension funds. This deep and widespread contribution from the private sector is the reason that various classes of investors become annoyed when governments complain about how little they invest in infrastructure projects.

The greenfield problem

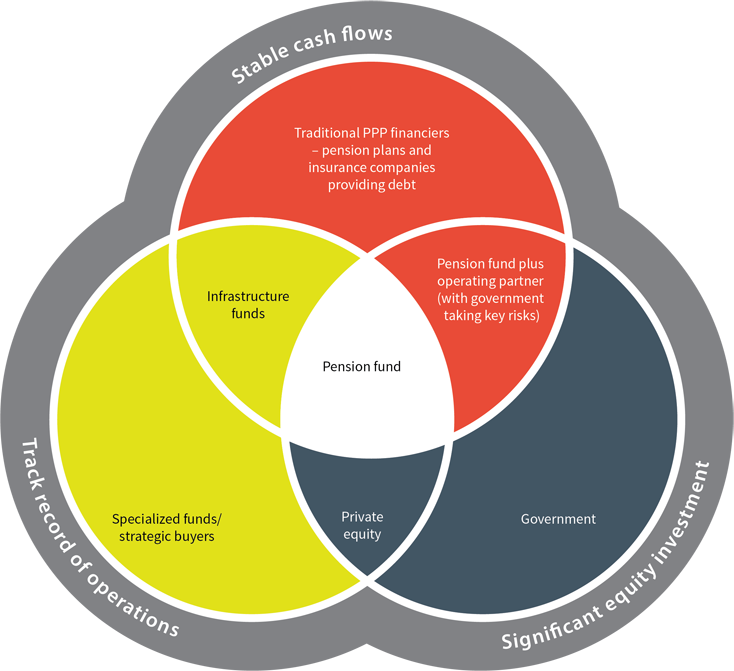

Even where governments are making full use of public-private partnerships to fund projects, the need for private capital remains acute. Governments simply don’t have the money to deal with infrastructure deficits. And, they tend to bring the world’s worst shopping list with them when they engage the private sector in discussions about equity investments.Private investors are looking for a combination of three things when deciding where to invest.

- Cash flow certainty. They want to know that the contract they’re signing with government and the regulatory regime they’ll face will guarantee a reasonably predictable return on their investment.

- A positive track record of performance. The private sector prefers dealing in assets and services that have known risk profiles, ones that will allow them to better predict a likely return under various scenarios.

- A sizable equity investment. They want to be able to deploy large tranches of capital.

Based on their typical preferences, if we were to visually plot various types of investors against these three dimensions, the result might look like this:

In my experience, government primarily approaches the private sector to finance projects that fall squarely into the bottom right-hand space of this diagram Government. Perhaps the most prominent example these days is high-speed rail. These projects require massive sums of money, and have uncertain risks related to ridership volumes, revenues, operating costs, and regulatory regimes. Small wonder that investors will only participate in these projects on an equity basis when governments promise to inherit the costs of these various risks.

Forward-thinking jurisdictions have come to recognize this problem and taken a different approach. They’ve created “asset-recycling” programs wherein they sell brownfield assets with long track records of performance in order to generate capital for new infrastructure. For governments able to deal with the politics of divesting public assets, this creates a far more productive set of discussions with investors.

The unsolicited proposal problem

Another basic truth is that some of the best infrastructure proposals—those that are poised to deliver the best productivity gains—are likely to come from industry as opposed to government. In these cases, private companies may be looking for a government grant (or contribution of land) to solidify the project’s economics, or seeking critical changes to laws or regulations.Governments struggle to deal with these unsolicited proposals. They are (reasonably) scared about acting non-competitively and picking winners. They often don’t possess the skills to determine how innovations will impact their objectives, or to negotiate complex deals with private companies. Worse still, they have a tendency to commit to pilots that don’t long outlive the government that initiated them.

The most successful jurisdictions are those that have created genuinely independent commissions or agencies with a mandate to:

- Identify infrastructure needs on a bipartisan basis, and set reasonably long-terms plans

- Ensure that these plans are future-proof by routinely engaging with technology firms to understand specific innovations that are on the fringe of changing paradigms

- Opine on unsolicited proposals from industry, and negotiate deals for government.